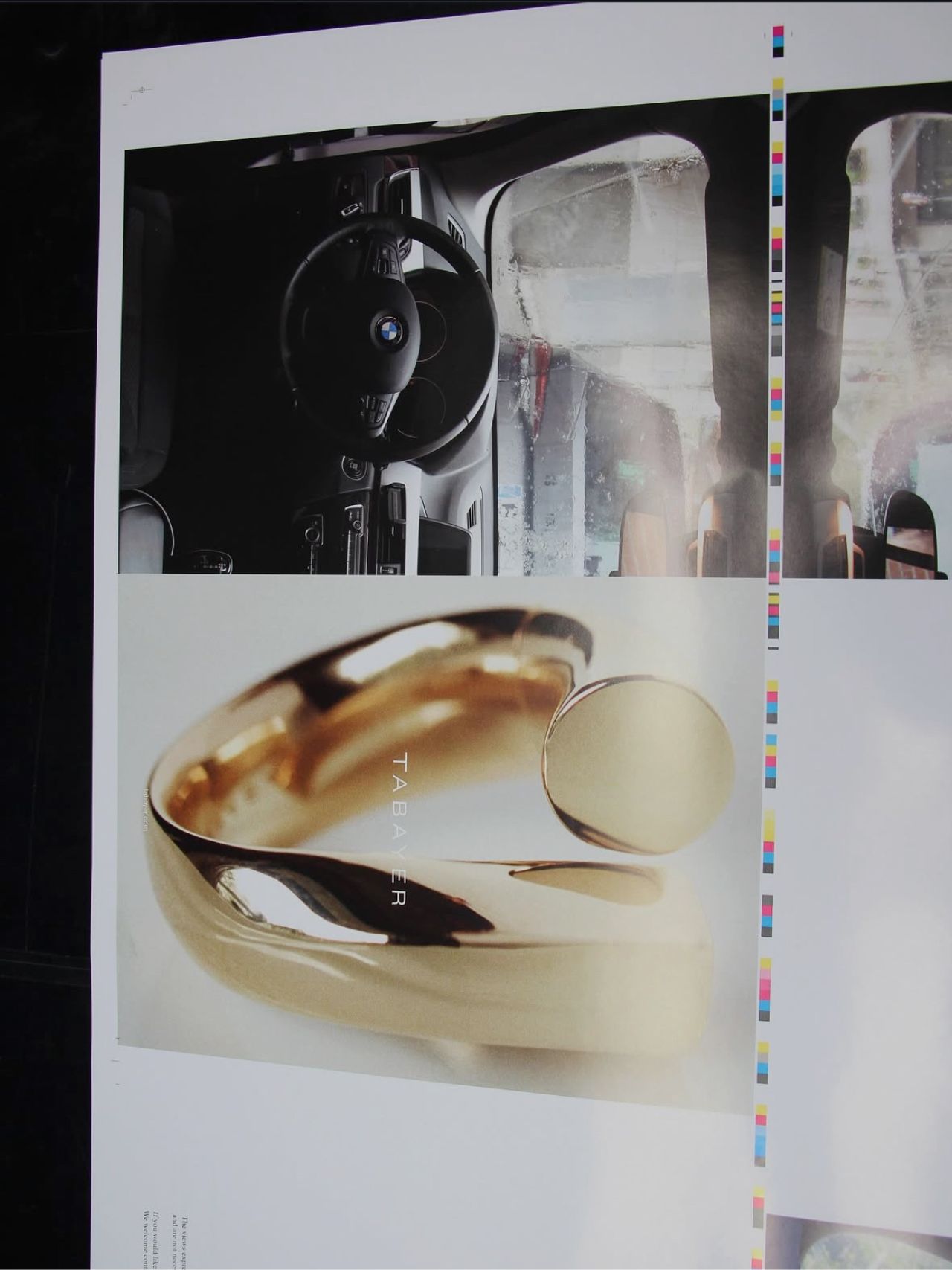

Running a brand today usually means chasing influence — fine jeweler Nigora Tokhtabayeva and Tabayer are after something else altogether: insight. With the publication of SUMMA Vol. II, the house shines the light of history on ritual, uncovering the many ways that the personal can become profound.

It’s so easy to find inspiration in 2025, with access to so much information, imagery — really the body of human knowledge. But with the endless expansion of our collective moodboard’s total surface area, it sometimes feels like there are fewer opportunities to go deeper, to see what’s underneath.

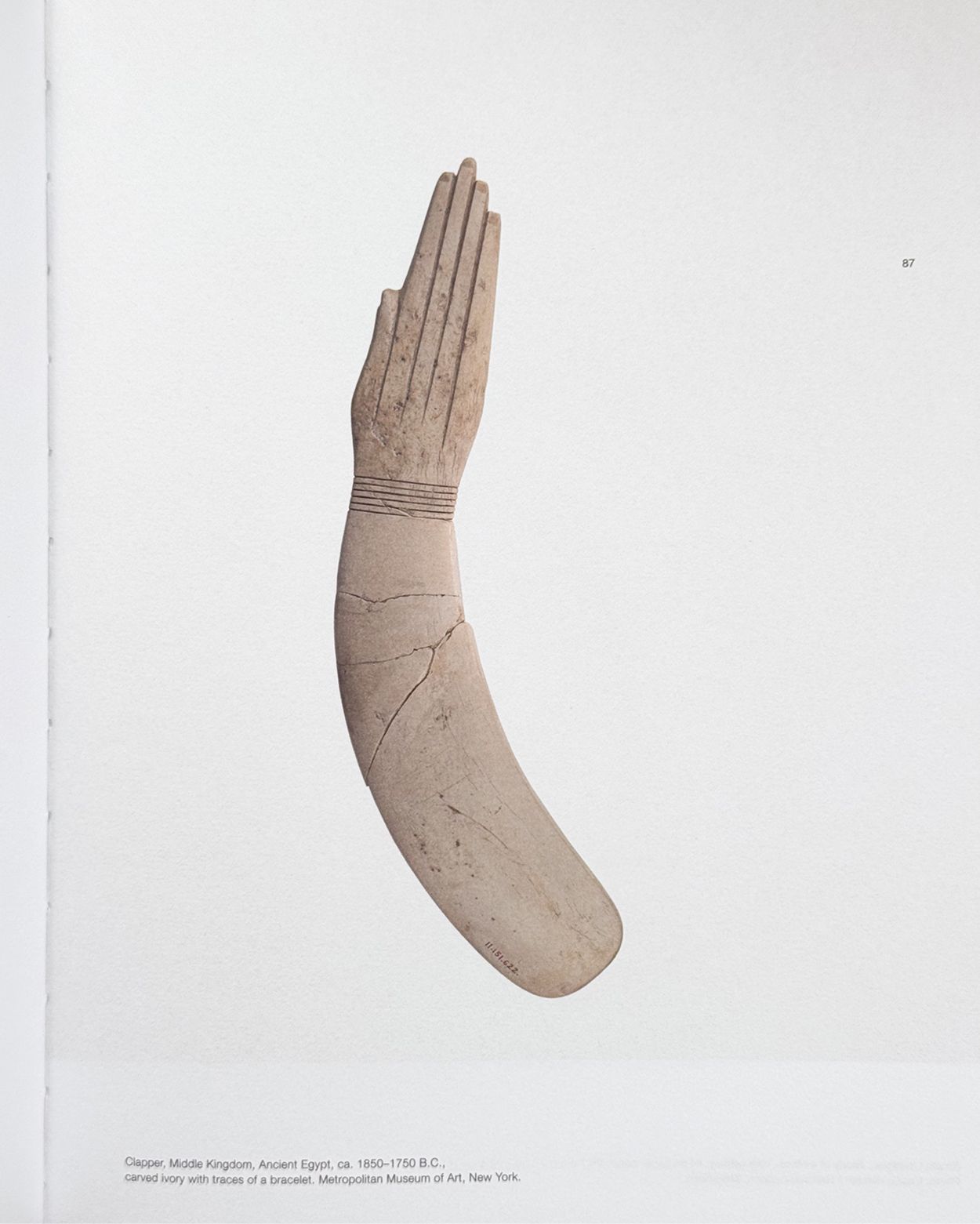

To understand more deeply what it means to be making objects of meaning today, Tabayer has created SUMMA, a contemporary revival of a medieval literary genre designed to investigate the totality of a specific subject. In SUMMA Volume two, Tabayer explores the expanse of RITUAL, bringing together photographer Yelena Yemchuk, writing from Megan Nolan, John-Baptiste Oduor, Kate Zambreno, Missouri Williams, archival selections from Clarice Lispector and Forough Farrokhzad and historical relics from across cultures and time. Why limit yourself to hopping trends when you can peer across the last 5000 years?

Éditions sat down with founder and designer Nigora Tabayer to talk about why it’s important to explore Tabayer’s purpose through the medium of SUMMA, and the ancient origins of her inspiration.

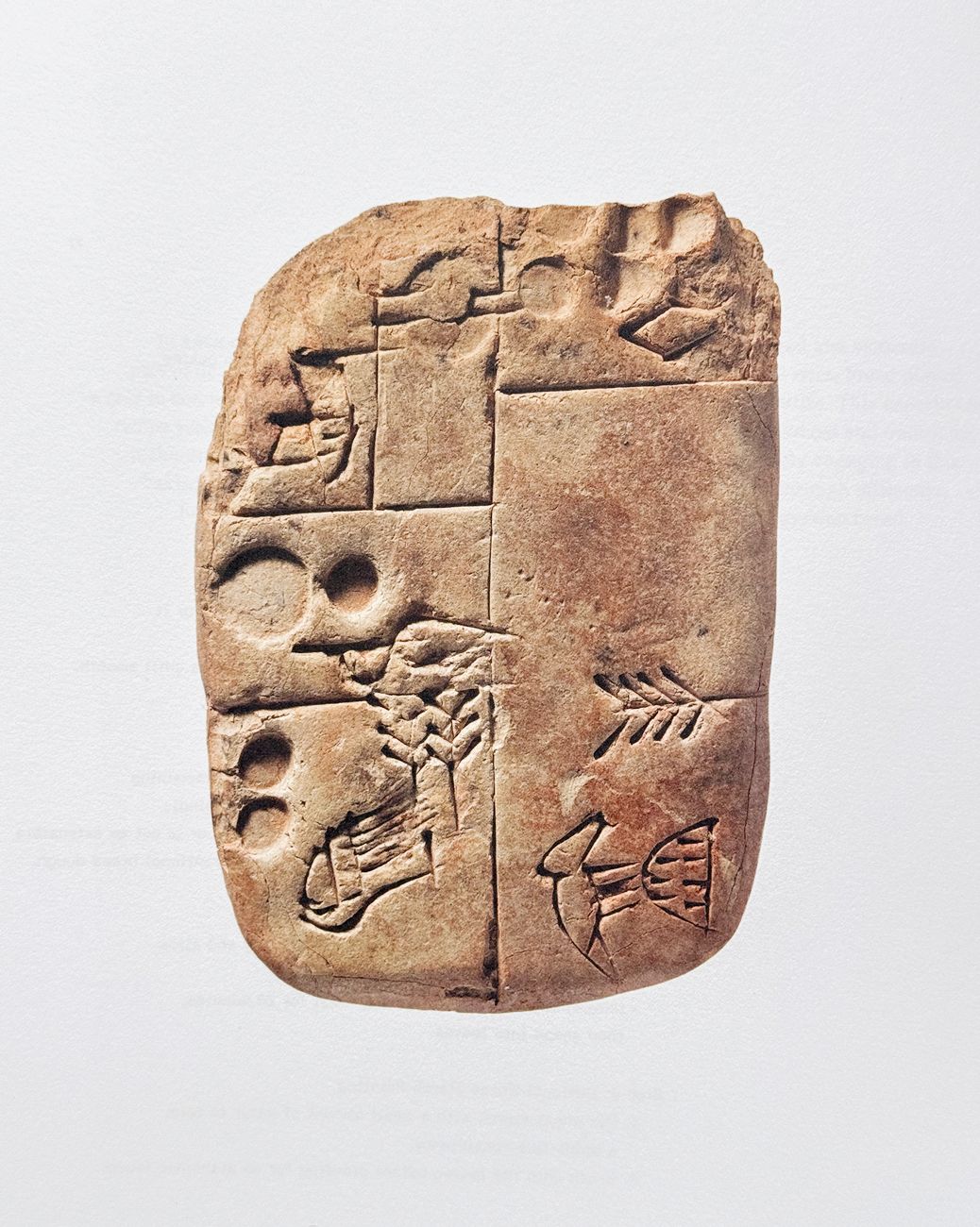

Cuneiform tablet, an administrative account concerning the distribution of barley and emmer, Jemdet Nasr c. 3100-2900 BCE

Cuneiform tablet, an administrative account concerning the distribution of barley and emmer, Jemdet Nasr c. 3100-2900 BCEÉDITIONS: So, starting from the very beginning, e.g. the world of antiquity, before we even get into SUMMA, I wanted to talk about your first collection — Oera.

NIGORA TOKHTABAYEVA OF TABAYER: Yes, Oera.

É: I was really fascinated by that — based on Inanna’s Knot, an ancient Mesopotamian symbol of abundance, prosperity, femininity and strength. It’s a graphic form, a tightly bound bundle of reeds in the shape of a spiral. I was reading around, it can also represent the prow of a papyrus reed boat, which is like a symbol of transition and a journey. Can you tell us how that inspiration took shape in the pieces from the initial collection?

NT: Well, I was born in Central Asia. I've always been surrounded by a lot of multicultural people, my family itself. I have a lot of international friends. When I was redesigning and rebranding Tabayer we started from scratch. We wanted to create a universal symbol of protection that is not tied to any culture and religion, but that still unites us. Throughout the research we came across Inanna. Her history is so deep, I felt like she was so relevant to now. Studying her, her personality and her powers, and then of course her knot that she created as a symbol of protection. People used to hang outside of the doors as a symbol of protection, to scare away evil spirits

Looking at the knot itself, the material, made only from reeds, it’ amazing how many layers it has. I was very intrigued, and looking at it, you can see how modern it could be, and had so much meaning, hasn’t it? It was a no brainer to to develop it into the universal symbol of protection.

To bring it to an even more modern place, we made it three-dimensional. And that's how we were inspired creating Oera.

É: I was looking at the stacked cuff in particular, which is just a striking take on that symbol, with many individual bars becoming kind of a single object in this bundle-like form. It really looks like that ancient pictogram! It has a one-from-many energy that can be felt in the other pieces, too.

It also has this shape-shifting quality of being both very simple and very sophisticated. But can you talk about the range of that concept and how it shows up in the design language of Oera?

NT: If we're speaking particularly about the new cuff that we just dropped recently, the principle runs through all of the Tabayer designs. In the cuff, you see the many rods joined to make one piece. In simpler pieces like this, the idea is present, but it’s a matter of how the shape repeats and balances each other. In that sense I feel like it's not just a design language, it’s become a philosophy.

É: Super exciting. Speaking of philosophy, I was also reading about the pictogram itself. From what I understand, not only does it represent the goddess Inanna herself, but it also can stand for the meanings around it at the same time. So there's this dual nature of being a physical thing, but also also an object of meaning. How does this dual nature show up in the jewelry?

NT: Growing up in Central Asia, jewelry is always more than just a beautiful thing that adds some shine to your wardrobe. It always has a spiritual connection, and most of the time acts as an amulet or talisman. Even the stones and everything have a lot of meaning in Central Asia. So it carries feelings, it carries memories and meaning. That runs through Tabayer DNA.

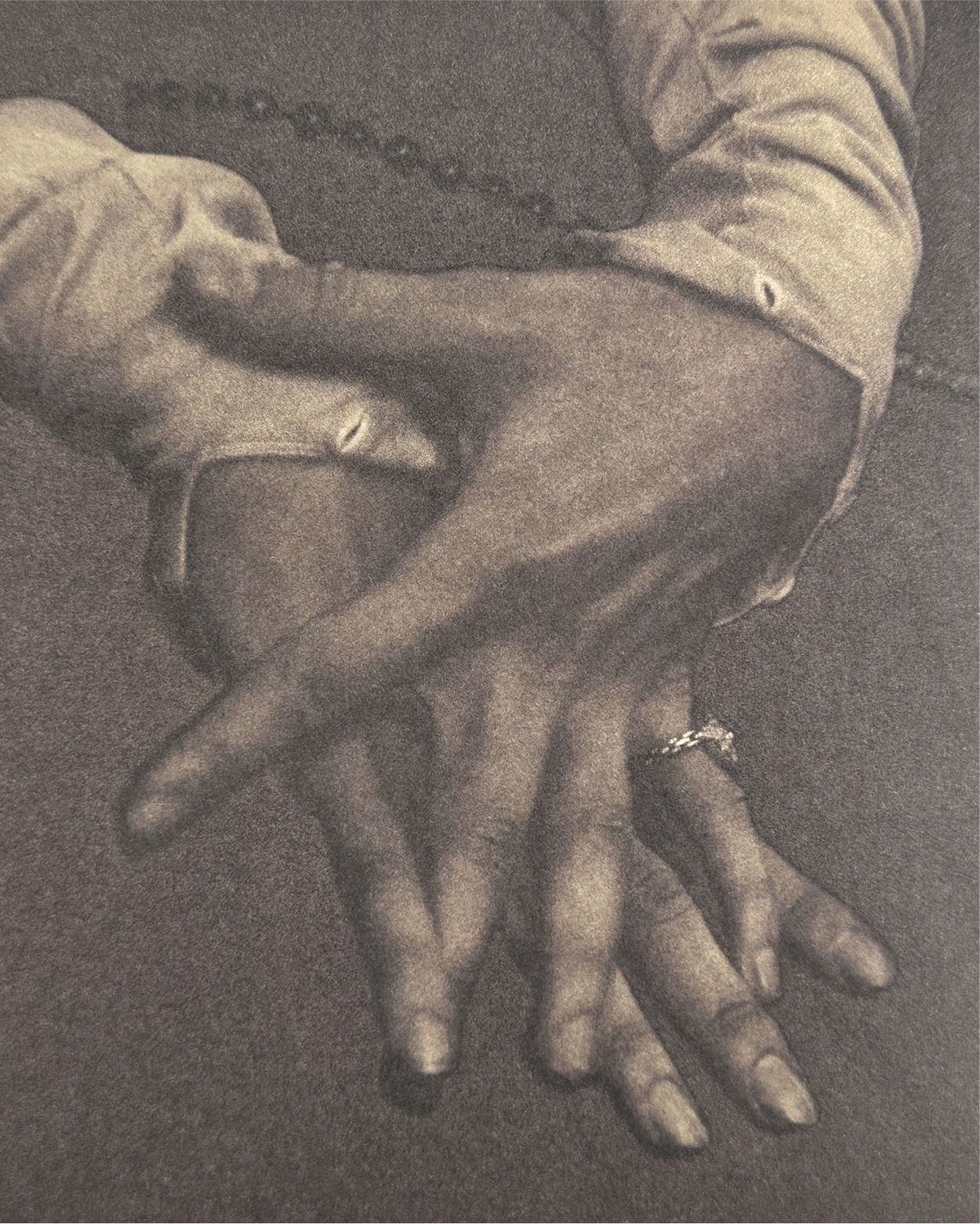

A piece of jewelry can mark a special memory, or it can offer comfort. Some people wear jewelry as a protection or reminder of ourselves. What matters to us is that a moment happened — maybe a special memory, a wedding, a birth, or anything, you know, it has has a lot of meaning. But even smaller daily moments still can feel very powerful.

É: Love that. Back to this idea of many things coming together to form one thing, I wondered if you thought about SUMMA in this way, too, many voices contributing to a singular exploration of an idea. Even from a production standpoint, the Japanese binding technique it uses has these little bundles of pages that are sewn together to become become one big book.

NT: There’s certainly a throughline, and a parallel to what we’re doing with the jewelry. The idea behind SUMMA is to bring together talented artists, writers, musicians, dancers — I think each has a unique voice, but together they explore and share an idea that’s more encompassing.

And yes, as you mentioned the book's binding reflects that it’s made from individual sections that tie together. I think it’s a beautiful way to show that differences can create a certain harmony.

É: That's beautiful. So SUMMA Vol. II is centered in rituals. It's sometimes easy to forget now, because you can buy earrings or whatever on like the TikTok shop page, but jewelry (as you mentioned) has always been used to mark ceremony or personal histories, the big beats. But you were talking about how maybe there’s something to the smaller moments, they add up and become these almost psychically charged objects.

Given your wide-angle frame of reference, what does it mean to you now to be making jewelry that connects with these ancient ideas?

NT: If you look at a lot of jewelry out there today, there are certain design motifs and ideas that are circulating. Being exposed to all of it, it’s really hard to come up with a new motif, and harder to make a piece of jewelry from it.

Tabayer goes back to history. For me it means that it means recognizing that we're not separate from history. We're made of history. Humans have always used jewelry as a way to to mark what matters — birth, love, death, change. Like I mentioned, it could also offer strength, you see kings and queens wearing a lot of jewelry.

People still wear jewelry for the same reasons, but nowadays our life is very fast, and things feel so temporary. Everything goes so fast and social media makes it worse. So to me, making things that last feels more important now than ever.

Untitled (Sun #10), Karen Arm, 2008, acrylic on canvas

Untitled (Sun #10), Karen Arm, 2008, acrylic on canvasÉ: Yes, feels like something universal you’re tapping into there. Even within universality, I think about the people you’ve brought together for this new issue — each of them approaches the subject matter of ritual from a totally different place. Between all of these voices, were there any universal truths that emerged?

NT: Yes, it was intention. Every one of these people think very carefully about how they spend their time and energy, whether it's something like writing or photography. Each of them transmutes the energy of daily habits into something very valuable. I think there is also a quiet power in doing things with care.

É: So much care — I think about how Jean-Baptiste has this little ritual of cooling his jewelry on the windowsill so that it’s cold to the skin when he puts it on. It’s very personal. How can jewelry kind of serve as a reminder for these smaller occasions?

NT: There are a lot of objects out there, but jewelry is a part of our daily life. I'm sure you have a piece like this too — for example wearing bracelets all the time, you may not even notice how they become connected to you over time, like some sort of memory.

If you take your ring or bracelet off, you start to feel for it, right? Because you become connected, you become one piece. So we put it on. We take it off. We touch it without thinking. You know, it's all becomes a part of us. These small actions can become so meaningful. They help us to feel present, connected — that’s how I feel it.

In simple words, jewelry becomes a gentle reminder of who we are, and what matters to us.

É: That's a really great explanation, and succinct too. What insights do you find in the historical voices you’ve included? From Noguchi to Forough Farrokhzad. Do they feel prescient or parallel to today? How do they play alongside these contemporary voices?

NT: Noguchi made art that felt very calm, powerful. It just looks calm, you get this calming sensation looking at it. But at the same time it's so bold and powerful, the volume, the shapes, the roundness. And speaking for Alzade, she wrote poetry that was so strong, but at the same time very emotional. To me each of these people weren't afraid to mix feelings with clarity, and that inspires me a lot in my work. If you look at our pieces, it has sharp edge, that transition to the smooth circular. You very distinctly feel the female and male synergy (we hear that feedback a lot from our customers). It's really really cool when you hear that feedback, because this is exactly what we were doing when we were designing our Oera.

É: What’s the design process like? Do you set out sort of concept first, or is it you sketch? How do you start to realize that duality and make an object that reflects it?

NT: First you find an inspiration. You go to the mood board, you know you find inspiration and start to develop the story behind it. Then you go on sketching multiple variations in order to really shape and the exact one. And then, after that, it’s like many layers, and facets that are considered in arriving at the final piece.

But I think the most important one, at least for Tabayer’s process, is finding connection to a story. It has to be more than a beautiful piece. It needs to have a feeling of connection. People really want more than just a piece of jewelry.

É: Do you draw first, or do you make mock ups? Talking Noguchi again, he made so many mockups of larger pieces at small scales or modest materials first.

NT: When I first started it was years ago it was just sketches. Now we have 3D printing which we use to make fine adjustments in scale and to the actual shape. That's like a final stage, of course, but before that it's really a lot of sketches. Better than pen and pen and paper, you know.

É: Totally — it’s cool you’re exploring these essential human forms that have been explored for so long, but in this very new way.

I always think about Janus, the two-headed god with a face that looks to the past and another that looks to the future. At Éditions we’re always keeping our head on a swivel, looking not just forward and back but all around for inspiration. We're not limiting ourselves to dance or photography or painting or sculpture or or architecture — it's all a part of you know what inspires us. When I look at Tabayer, I really relate to the way you spend serious time with mythology, religion, philosophy, poetry and literature.

What’s resonating for you across all of that as someone who’s making work right now? Since your affinities span millennia, how do you kind of locate yourself in our collective past?

NT: Well, today, I think people are looking for a deeper meaning. I know I keep repeating myself, but that's what I really strongly believe in. Tabayer is built on the idea that beauty and intention really go together. I want I want to make jewelry that feels timeless, not just because it looks good, but because it says something and it stays close to to the heart. I don't copy the past, but I learn from it. The past can teach us a lot.

I think about being a parent I look at past my mistakes and teaching my kids how to be better. I mean, there's always so many things we can bring from the past for our kids, friends, or whoever it is. So that's what I think about with design.

É: What about the face that looks forward? Tabayer feels like it already has a foot in the future. What are you excited to explore? What are some materials you haven't used yet?

NT: You know, I always wanted to explore obsidian. I think it's very strong. It looks very natural and it has a protective protective element, so obsidian is on the top of my list.

É: Obsidian is so alluring. It's got that jet black mystery and quiet power. Almost feels like it couldn’t have been made by nature but somehow it is, just wild.

You pointed out the little bracelets that I’m wearing. My parents live in Oregon now, and these are just from little lapidary, this man named Seamus, and he has, like a rock store. I was fascinated by both of these. Specifically, this one, though, which is called red turquoise — you think of turquoise as a color, but it’s also a kind of stone. Red turquoise is such a beautiful contradiction of terms, I love it even though it only cost $30. I also love Jasper.

NT: I don't know if you’ve seen our collection that we dropped in 2024, but we made a beautiful choker made of jasper and a bangle. You can do so much with it.

Cantabrian Coast, Alessandro Furchino Capria, August 2024 — exploring the windshield as both frame and filter, where constancy of angle and position creates a rhythm—difference revealed only through time, place and light.

Cantabrian Coast, Alessandro Furchino Capria, August 2024 — exploring the windshield as both frame and filter, where constancy of angle and position creates a rhythm—difference revealed only through time, place and light.É: Do you have a dream contributor you’d like to work with? Can be alive or not.

NT: Barbara Hepworth

É: Oh my god, I love Barbara Hepworth [picks up a Barbara Hepworth book from the shelf]

NT: I like your Zoom background. You have everything there (haha). Yes, like her sculptures feel really peaceful and powerful. Her art is also in the Tabayer’s DNA alongside with Noguchi, you can see that the dimensionality and the curves, just amazing.

É: What’s your favorite art book at home or in the studio right now?

NT: Currently, I have Alberto Giacometti’s work out all over. I love his work.

É: What’s next for Tabayer after the launch of SUMMA Vol. II?

NT: I think we'll keep exploring how to create jeweler that upholds oru ethical values and to tell stories in new ways. We're very young and interested more in repetition rather than the pressure to always be innovating on something new. I plan to continue doing what we're doing, the same story but at a bigger scale.

É: A spiral that keeps on growing.

Antoni Tapies, Snake in a Square, 1991, mixed media on wood

Antoni Tapies, Snake in a Square, 1991, mixed media on woodFROM THE EDITORS OF SUMMA VOL. II BY TABAYER

É: Regarding the contributors, including the likes of Yelena Yemchuck, John-Baptiste Oduor, Missouri Williams et al, each approach ritual from such different places — what was the thought behind bringing together this particular group of people?

SAMUEL RUTTER & EMMY FRANCIS: Part of the magic of making a magazine is its curatorial aspect. It's more like a group show, than say, a career retrospective, because you have the opportunity to bring together different voices working in an array of styles, and thread them together with an organising idea like ritual. For Summa, we wanted to explore how ritual is a shifting, almost chimeric concept.

É: What connections emerged between the stories past and present? Were there parallels that emerged between voices from the archive and the present-day contributors?

SR&EF: It was exciting to see the ways the past connected to the present through ritual. The very specific context of the Manet paintings that are key to John-Baptiste Oduor's essay, for example, gain new resonances when you consider they begin as social documents of 19th-century France, but when viewed through his writerly prism, they have something else to say about how life is lived by a Black man in Washington DC in the early 21st century. In Missouri William's essay, some of her ambivalence about the state of modern marriage is assuaged by connecting it to mediaeval tradition, while Kate Zambreno's approach to minerals—thousands of years old in some cases—helps her track the fissures and veins of her own family history.

É: Now that the boundaries of time and geography have all but disappeared, what does the genre of SUMMA mean in a contemporary context? What is its potential in the information age?

SR&EF: There’s a paradox at the heart of the information age. Sure, it's possible to digitally preserve the ‘information’ we create — but it's not free, and it's not forever. There's a certain charm to the old internet, to links that no longer work, to a website that hasn't been updated in twenty years. It has also redefined the physical object. Physical media like magazines and newspapers can float liminally between permanence and impernanece — we tend to throw away a newspaper, but a beautifully crafted magazine might find its way to a bookshelf, a coffee table, even a bathroom, for many years after its issue cycle is over.

We also think that the sort of detail rich, contemplative writing in SUMMA deserves the generous texture of print, the comparative slowness of physical media. You might have thirty tabs open on a computer, but you can only read one magazine article at a time.

É: As editors, who is the SUMMA reader that you have in mind?

SR&EF: As a project of Tabayer, we hope that the SUMMA reader is someone who appreciates the depth of contemplation that goes into work that might appear seamless, effortless. A spirit of discovery and adventure is always nice, and an openness to consider the way the past connects us to the present and helps us embark upon our future.

É: What's a lesson about ritual that can be taken away from SUMMA Vol. II?

SR&EF: Ritual can be rooted in something simple or complex, something new or something very, very, old. Whatever it is, we hope that it connects you to the world and those around you, every single day.

MORE THOUGHTS ON RITUAL FROM FRIENDS OF TABAYER AND ÉDITIONS

ALIA RAZA, PERFUMER AT RÈGIME DES FLEURS

‘I have an unusual ritual that no one knows about. After dinner, I like to walk up and down my apartment, back and forth, usually with music on, occasionally in silence. You could call it pacing, but I’m not nervous when I do it, I’m relaxed. I guess it’s a way to wind down without sitting down, moving my body without the stimulation of being out in the world. It’s a bit eccentric, but it works. A new kind of me time.'

ASH ROBERTS, PAINTER

‘I wear a cartouche around my neck that I believe carries totemic power. My Grandfather got it in Egypt years ago. It spells out his name in Hieroglyphics. He was a big traveler and a huge influence in my life, both in his style and his warmth. It’s a calming, centering totem in my life, and I think a way to continue to link the two of us spiritually.’

ELORA JOSHI, DESIGNER AND FOUNDER AT JOSHI-GREENE

‘Taking quiet time in the morning to think and catch up on tasks is a necessary ritual in my life. The hour or two directly after waking is when I am able to jot down my thoughts, read, catch up on emails, and more. I do this over a hot drink — either a coffee or matcha depending on my mood — each morning.’

SIMONE BODMER-TURNER, SCULPTOR

‘When I am at home in Massachusetts I walk every morning in the woods and fields, before coffee, without my phone, and with the dog and a big bottle of water. This begins my day every day with quiet, connection to nature and this amazing animal I get to share life with, and light movement that warms my body up gently.’

TILLY MACALISTER-SMITH, DIRECTOR OF EDITORIAL AT CHRISTIE’S

‘I’ve quite recently (in the past six months) started taking a dawn morning walk. I’ll go solo or with my dear friend who I have the fortune to live across the street from. It starts at 5:45 — street sweeper hour, the shift change of as many people waking up as are going to bed, and the occasional insomniac octogenarian. It isn’t pretty until you get to the water. There: horizon; fishermen with their nets and rods propping up the bay; river birds flying low over the water scanning for their breakfast. In the distance you can see the Statue of Liberty (withering?). In one sweep, the sky goes from grey to lilac to blue. The air is fresh at the start and muggy by the end. I carry a weighted vest because my body is too tired to run, but the load feels satisfying, necessary.’

SARA LEVINE ON OBJECTS OF MEANING

My husband gifted me a 18th-century cameo that he bought in a shop in Rome. I lost it in walking around Paris and was devastated, but, almost magically, I found it laying on the floor of my hotel room in Seoul a few weeks later… a mystery I’ll never solve and a wildly powerful object!

MORE ON TABAYER

Founded in 2021 by Nigora Tokhtabayeva, Tabayer is inspired by the power and symbolism of jewelry. Tabayer nods to the multifaceted woman: an independent, feminine, and empowered individual who embodies a unique balance of vulnerability and strength. This special duality is echoed in Tabayer’s modern, minimalist designs.

Tabayer’s second collection, Zorae, launching Fall 2025, is inspired by the ancient symbol of the sheaf, an emblem of unity, abundance, and resilience. Sculpted in gold and accented with diamonds, Zorae’s flowing silhouettes express strength through interconnectedness, becoming a modern talisman of harmony and grace.