The best new gallery in New York is actually in Sag Harbor. Shooster Arts and Literature was brought to our attention by a friend who couldn't believe we didn't know about it already. Naturally, we had to drive out to the Hamptons to find out what exactly it was that we didn't already know.

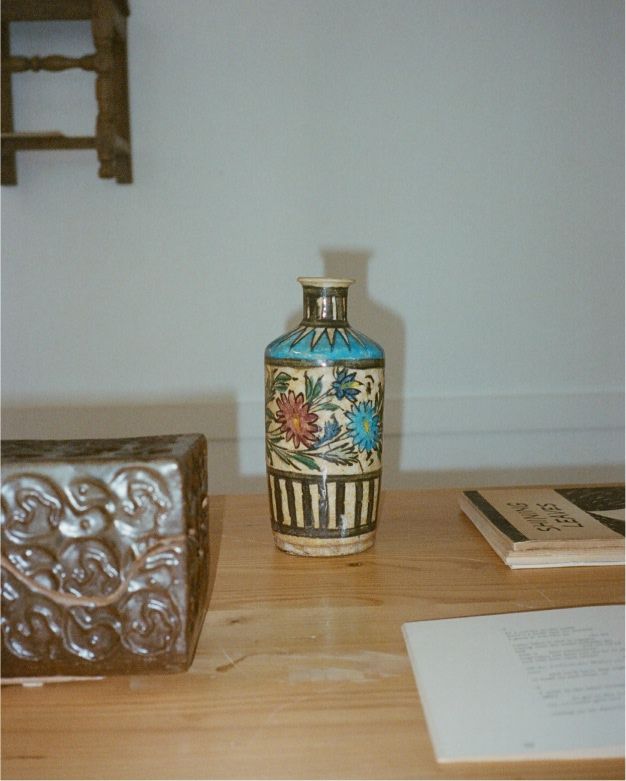

Shooster Arts and Literature is a new exhibition space, store and creative concern from art director turned gallerist Lauren Shooster, rooted in outsider art, collectible furniture, uncommon ephemera and perhaps most importantly, poetry.

We use the term ‘gallery’ here because it’s the quickest shorthand for what’s going on over there, but the proposition of SAAL goes beyond the white box format to ask: What does it mean to actually live with all of these important things? The answer may just be very the dual-identity of SAAL itself, both an exquisite home and shoppable gallery space at once. On a Summer visit to the Hamptons, we figured it was worth asking a few more questions.

ÉDITIONS: Based on the sheer volume and careful curation of objects, furniture, collectibles, textiles and books in your inventory alone, this first manifestation of SAAL feels like it has arrived fully-formed even though it’s brand new. How long has it actually been in the works?

LAUREN SHOOSTER: I’ve been collecting seriously for the past seven years. I had always wanted to do something like this since my early days of art direction, maybe even since 2014. But then I didn't know what that was or how to do it, I didn’t have enough experience — I didn’t fully understand who I was at the time yet, or how my interests related to one another.

I started conceiving of the project, or rather taking action with the project in 2023. I was unable to work due to an accident I had a few years ago. Things became difficult — I was in my bed, laid up, I think I was looking for paintings online. I looked around my room at all my belongings and I thought, ‘I have all this stuff and I have nothing to do with it, nobody to share it with…’ and that’s how SAAL was born.

É: Did collecting over the years help to form the identity around SAAL? Rather than setting out to collect specific things, did the things themselves together create some specificity?

I think so. I don't know if you relate to this as a collector or an art director, but it feels like we all have a tendency to archive or package things a certain way. After I started collecting, I was like, I’m just going document all of my acquisitions.

Once I started looking at all the thumbnails and seeing everything together, because it's very different to see something in a spreadsheet versus seeing it, like, in an apartment setting — I thought, ‘Oh, there is a clear visual language here, and there is some connection between all of these things.’ It’s something even that runs deeper than just personal preference, there is some kind of ethos or point of view behind all of this.

É: I was struck by is that intermingling of fine art and furniture, collectible books and objects, Known artists and not known artists (like your dad, for example). When did you start making those connections?

LS: Putting them all together, and seeing the lay of the land, but… through therapy (haha). It's a very Freudian push-pull of, ‘I’m nothing like my parents, I’m everything like my parents’ and on and on you go. I realized that my taste is really an amalgamation of my mother's taste and my father's tastes. My dad collected masks and pottery from all over the world, primarily Central and South America, and Asia. We had all these Mexican blankets, stacks and stacks of Mexican blankets, almost like how Donald Judd collected them. This is long before I knew even who Donald Judd was.

My dad also had an interest in modernist architecture. We had some Breuer chairs growing up, and I lived in a house that was very strange. We had this Rousseau painted TV cabinet that was super tacky and kind of hideous, but amazing. Next to that is a Breuer chair, and next to that is my mother's, Monet impressionist lithograph of whatever the fuck, and it was just kind of offensive, but it worked?

For a long time I shied away from the things that shaped my formative visual identity, things that were very spare and very intentional, not maximal at all, soft, muted colors, brown and greens, natural feeling and subtle things. Neither of my parents were subtle. I realize now, sitting in my room and looking at all of my shit, and thinking everything that I’ve ever interacted with or encountered has informed my visual lexicon.

É: Totally. Feels deeper than aesthetics, though — the way that you connect things feels very familiar. At Éditions we’ll share a sculpture made of nylons by Senga Nengudi, a poem from René Ricard, photos from the Provoke movement in Japan and a Prouvé chair all within the same newsletter. I can't always explain what the connection is, but I can feel it when it's there. Maybe it’s frustrating to ask this, but what’s the energetic through-line for SAAL?

LS: I have a lot to say about this subject, be careful what you wish for (hahaha). It's actually inspired by the person I named my dog after (I think we talked about this in person) — she’s named after Etel Adnan.

A quote of hers that stood out to me when I first encountered her writing: ‘Your real home is your life.’ I think that that has always stuck with me.

So if I were to say, what is my perspective or how are these things related? This is a diary of my life — every heartache, family tragedy, it's my accident, it's every job I've ever had, it's every book I've ever read. Quite literally, it's really my life on display. In that way, some of the connections were unconscious, I mean I think that literature and paintings influence my taste in furniture, space and architecture.

Ultimately there has to be a little bit of freakiness involved, a little perversion in whatever it is — an object or a painting or a book. Never self-conscious. If I were to say in one word what connects everything it’s fearlessness. A lot of this is outsider art, making something because you have to, you don't have a choice, it's not for anyone else.

É: Feels like that’s the reason you can also stage Mario Botta Seconda chairs next to ornate 1930s hand-carved woodwork and 1980s gallery monitor TVs. Even though they’re objectively very different, there are deliberate choices behind the designs.

LS: Yeah — they’re not shy of committing to the idea behind it. Something interesting there about the energy as opposed to just the visual language, which makes it possible for a tension of opposites. I hate to say it, but there’s a certain masculinity to some of this stuff that reflects my personality in some way, and maybe even my appearance in some way.

Um, and then there's another way it all feels really kind of understated and feminine, and soft. There’s a bit of humor in all of it to — it’s funny, it's sad, and it's serious all at the same time

É: There’s enough space around everything to help make those connections, too. A lot of dormant potential energy — you see those gallery TVs in there and start to wonder, ‘what would be playing on there if something was playing?’

LS: Yeah, totally.

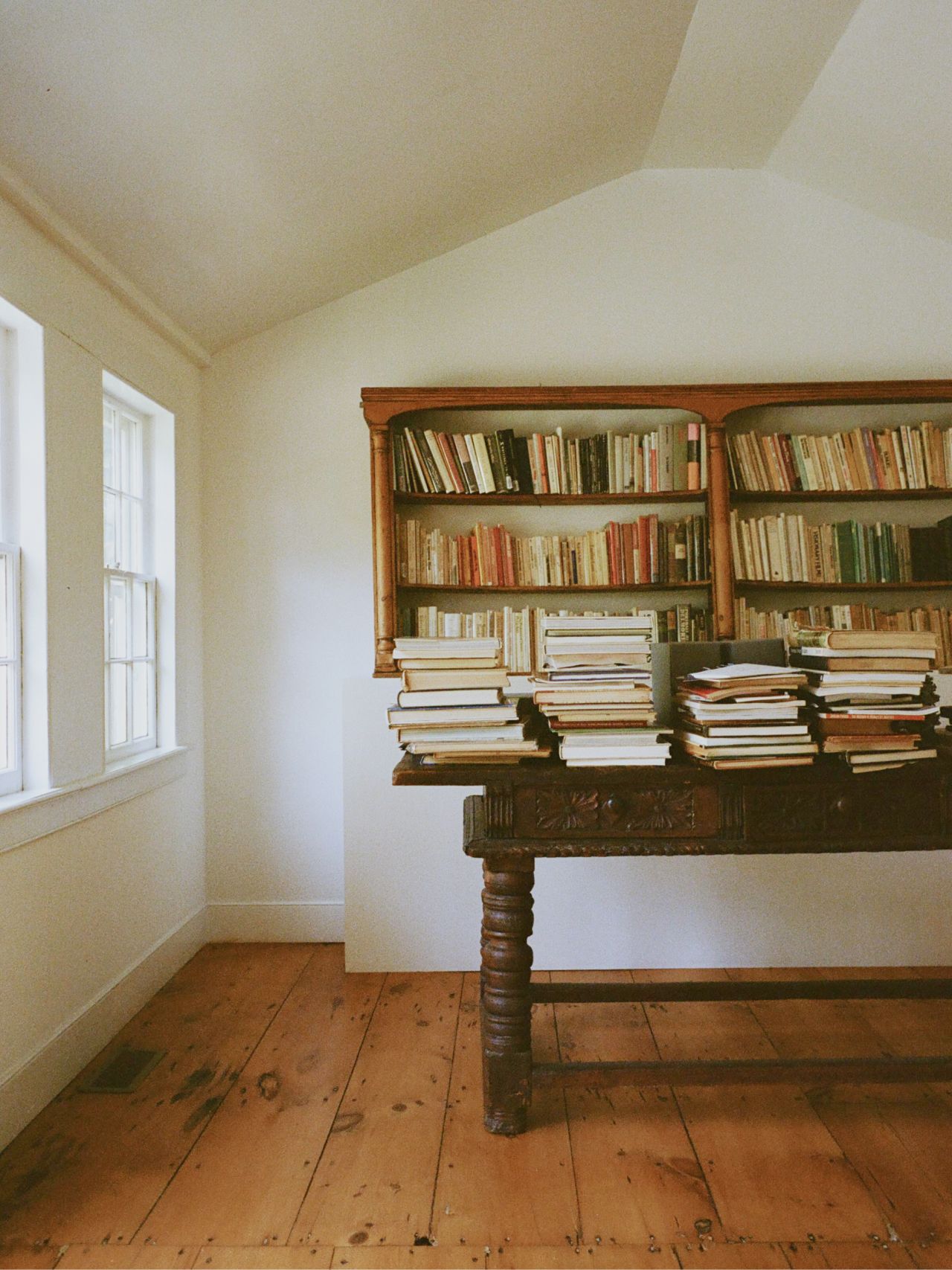

É: The gallery space is very connected to your home in an energetic sense. It’s also right around the corner. It feels like there’s a porous barrier there, maybe there's not a barrier at all in your mind. The inventory, the way you’ve brought it all together, feels so personal. It also feels like the right customer could come in and outfit their ideal artist home in a one-stop shop — get the chair, the library, the objects, a Rietveld desk and maybe even a bedframe. This is such a departure from the white box gallery idea of art removed from the home or the living space. It feels so approachable. Is this sort of the value proposition of SAAL, showing how to live with art, to live artfully?

LS: Yeah, I mean, it's a little, um… dangerous of me to do, which is kind of fun… but I do it. It's like, if I spill something it means that I, as the founder of SAAL, personally spilled something on the sofa, you know? So being able to live with these things for real shapes how it’s understood by others. It creates a reverence for the thing, because you know, life isn’t clean, and I wanted the inventory to reflect that. Living with it all somehow gives life to everything which might otherwise feel lifeless in a traditional gallery setting.

É: Sag Harbor has a fascinating history as a hub for printing, and it’s long been a refuge for artists, writers, etc. What drew you to it?

LS: I mean, I think that very thing that you're describing. I’m from Florida and I wanted to be by the sea. I knew that being closer to nature would be better for my health condition. I also wanted to be somewhere that any of the new school artists frequented, because that's kind of my primary interest as far as literature goes. I figured if it's good enough for them, it's good enough for me.

É: Strong energy. Now that you’ve established this beautiful place here, I also heard that you’re going to be publishing original works and putting out new work. How do these new ideas expand on the premise of SAAL collection?

LS: I wasn't interested in just creating another gallery. I don't think there's necessarily a need for another gallery. To be totally frank, I wanted to do whatever the fuck I wanted. Obviously, there's a major intersection between art and literature as academic practices, but I think on the receiving end, for the buyer, that's not always the case. Literature, particularly poetry, has been historically undervalued. I want to convey its importance to collectors.

As a society, we’ve sort of decided that art, photographs, and picture books are more accessible [than literature] for whatever reason. But what about language? I felt it was really important for me to fold that into the conversation with SAAL.

É: You can definitely feel that conversation happening here.

LS: Yeah, and the response has been really positive, and has really set the gallery apart from similar institutions.

Just going back to how these things are all interconnected, iall the artists involved in one way or another are what make SAAL what it is. There isn’t necessarily a clear 1-to-1 connection between what their backgrounds are or what their formal education is I think it’s people that being just wholly themselves.

É: Amazing. What’s up next for SAAL?

LS: Partnering with some prominent literary publications and historic estates. I feel very passionately about our ephemera collection, and I’m working on some exciting ways that we can represent that portion of an estate’s collection. This is something that a lot of museums and institutions overlook.

We'll also have some interesting readings coming up, new curators coming into the fold, partnering with other like-minded people to kind of make it grow.

I also think that New York City might see a version of SAAL appear.

É: That's a very tantalizing note to end on. Thanks so much for giving us a peek behind the scenes.

SHOOSTER Arts & Literature (SAAL) is a living gallery of fine art, antiques, and rare books. The research library includes prose, poetry, philosophy, art and non-fiction works.

Located in the village of Sag Harbor in a historic ship chandlery building, the gallery features works by artists Bruno del Favero, Purvis Young, Lewis Smith, Jack Savitsky, Justin McCarthy, Claes Oldenburg, Roberto Matta, Thornton Willis, Jenny Holzer, Josef Albers, Pablo Picasso, and Richard Long; designers Gerrit Rietveld, Guy Rey-Millet, Jean Prouvé, Afra & Tobia Scarpa, Josef Hoffmann, René Gabriel, Pierre Jeanneret, Achille Castiglioni, Shiro Kuramata and Charlotte Perriand; photographers Vivian Maier, Emil Otto Hoppe, Helmut Newton, Vivian Maier and Werner Rohde; authors Alice Notley, Rene Ricard, Thomas Lux, Ron Padgett, Bernadette Mayers, Louise Glück, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Diane Wakoski, Eileen Myles and Allen Ginsberg.

A significant portion of the collection is dedicated to unattributed works from as early as the fourteenth century to the present. Services include product sourcing and authentication, staging and rentals, brand development and design consulting in the arts and interiors.

SAAL houses over 300 artists, writers, and designers works in a non-programmatic setting.